The prime minister has announced another shift in India’s vaccination policy in his address to the nation. It has not come a day too soon.

The Supreme Court had expressed concerns about the policy in place and several chief ministers of states ruled by opposition had demanded a change.

Given the situation, are more changes in vaccination policy likely in the near future?

Twists

India started vaccination on January 16, 2021 when the first wave of coronavirus was ebbing with daily cases down to 15,144 from the peak of 97,894 on September 16.

The prime minister had declared victory over the disease and he even boasted that while rich countries were experiencing a rapid spread of the disease, India had managed to control it. It is this stance that led to a relaxed vaccination strategy and which has turned out to be a blunder.

According to reports, India did not order vaccine doses in advance, unlike what many of the rich nations did. The latter paid advance to vaccine manufacturers to book billions of doses starting July 2020. India placed orders on SII on January 10 for the vaccination programme starting January 16, 2021. So, SII which is supposed to have the capacity to produce 1 billion doses a year did not produce and stock up doses in advance. It also catered to foreign orders and exported 60 million doses.

Complacency also led to a very slow start of the vaccination programme. One crore frontline workers and health personnel were to be vaccinated by end of February – in one and a half months. At this rate the nation would have taken 18 years to vaccinate all the citizens.

It was clear that vaccination was essential to deal with the disease. Lockdown is not a cure but only a means to slow the spread of the disease. Only a medicine or a vaccine can help cure the disease but no medicine is in sight. Vaccines have been developed rapidly and nations have allowed emergency use, given the scale of the disease.

But vaccination is not a short run solution. There can only be a finite supply so that enough vaccines cannot be available to vaccinate everyone in a short period of time. There has to be a queue based on prioritisation. In other words, vaccination of the population can only be a medium to long run solution, given the availability of vaccines.

The Centre did suggest a queue but the urgency was missing.

From March 1 to end July 2021, 30 crore elderly and those with co-morbidities were to be vaccinated. This meant 12 crore doses per month or 4 million per day. At this rate also it would take about 2 years to vaccinate everyone.

When these policies and queues were announced the wave was abating and a possible second wave was not anticipated. Kumbh Mela, assembly elections, etc., were planned believing that normalcy had returned. The public also became lax in following the required precautions.

The second wave started in mid-February after daily cases had reached a low of 9,121 – not a small number. By mid-March the daily infection reached around 40,000 but the government still did not believe a wave had started.

Panic-induced changes in vaccination policy

Panic set in in April. Cases crossed the previous peak on April 4 and rose exponentially to above 2 lakh on April 14. Mumbai and Maharashtra started a lockdown that day. Delhi went in for lockdown on April 19. The health system started to breakdown in the metros and reports of distress from all parts of the country, including rural areas, started appearing.

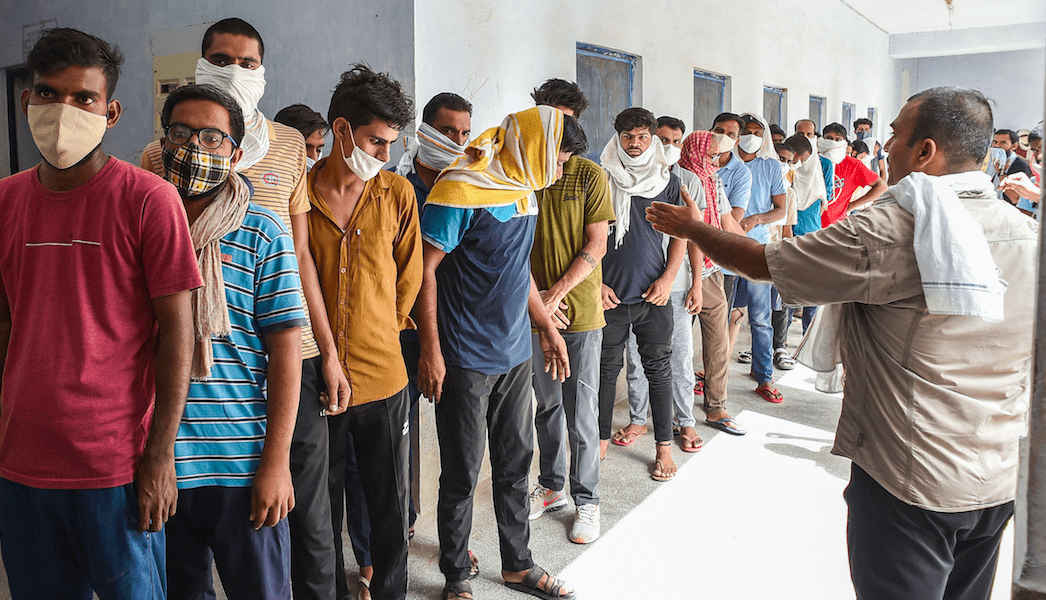

The importance of vaccination dawned on everyone. States started to clamour for vaccines to rapidly inoculate their population. Since enough doses to vaccinate rapidly were not available they wanted the freedom to procure doses. Businesses facing lockdown and closure demanded vaccination for their workers and this led to the demand for vaccinating those in the age group of 18 to 44 years. In the second wave, many young people got infected and succumbed to the disease, so the pressure built up to reorder the queue set up in January.

The Central government came in for severe criticism for failing the nation. It needed to deflect the blame. So, it changed policy on April 19. It knew that more doses of vaccine were not available and the blame could be shifted to the states by giving them a free hand in vaccination.

The queue established was given up and all above the age of 18 were made eligible for vaccination. This was bound to fail since more vaccine were not available for love or money. States that floated tenders to buy vaccines quickly found out that there was a global shortage – even UNICEF has not been able to get enough doses.

From national to sectional policy

The private sector was allowed to buy vaccines to inoculate its workers. Multiple prices were allowed. One price for the Central government, a higher price for the states and a yet higher one for the private sector. This was convenient since private hospitals and the manufacturers of vaccines found a way to make a substantial profit.

The physical queue was replaced by market forces with money determining the queue. States that were to vaccinate the bulk of the people could not get enough supplies while the well-off and the businesses could get vaccinated at ease and so could their employees/workers. There were car lines and vaccination at private colonies. But, little of vaccination in small towns, villages and urban slum clusters. To be fair, there was also vaccine hesitancy among the poor. Their faith in state policy is so low that some hid in the forests or jumped in the river to avoid getting vaccinated.

There was no way that this policy could succeed in vaccinating everyone – enough vaccine doses are just not available for such a free for all. So, the prime minister in his address laid the blame for failure of vaccination strategy squarely on the states and the critics.

The latest changes do not disturb the access of the private sector. They will get 25% of the available vaccines and will be able to vaccinate the well off and their employees. The idea is to restart production.

It will also ensure profit to the vaccine manufacturers and the private sector hospitals. But, the organised sector is only 6% of the employment and even if we take their families into account, this sector will get a proportionately larger share of vaccines. The implication is that the unorganised sector will get a proportionately smaller share and will not be able to restart work soon – one more hit to this sector suffering since demonetisation.

The governments also need to tackle large scale vaccine hesitancy through a mass campaign but that is nowhere in sight. How important this is became personally clear to me last week when a political party organised a discussion with their village level workers in Uttar Pradesh. They reported large scale illness in April and May, lack of facilities in villages and a sporadic vaccination drive. Importantly, they reported hesitancy due to multiple reasons, one of them being that vaccines were believed to be leading to illness and death.

Has triage become necessary?

A queue requires prioritisation. A judge recently argued that the elderly who have been given priority in treatment have lived their lives and instead the priority should be given to the younger people who have their lives ahead of them. Triage may also have to be followed for the vaccination queue since vaccines are limited in supply.

It is known that the elderly and especially those with co-morbidities are more vulnerable to severe attack of COVID and death than the younger cohort. So, to reduce death and severe cases in hospitals one needs to vaccinate the elderly and those with co-morbidities. But the elderly are mostly retired and can stay at home and, therefore, less exposed to the virus, unlike the younger people who are working and have to go out of the home and face infection.

The family is a unit and any death sets it back. If the elderly are left out of the vaccination programme, the number of deaths will rise and many more families will get affected. The young who have to go out to work also tend to be lax in following COVID appropriate behaviour and therefore catch the disease. They can carry the disease back home and infect the elderly. Finally, the health system may also be unable to cope with many more severe cases and in a vicious cycle more may die and cause crisis in more families.

So, there are strong cases for first vaccinating the vulnerable or the more exposed younger cohort. The choice may depend on where the nation is in the wave. When the cases are few, the elderly may be prioritised since the younger people will be less prone to infection if they follow the appropriate precautions. In the intense phase of the wave the priority may have to shift to the younger people since they will become more vulnerable. Rapid vaccination is the only way that society can avoid having to make such difficult choices.

Prospects for rapid vaccination

Government is claiming that July onward, availability of vaccines will improve and a crore will be vaccinated daily. Trials for vaccinating children are going on so that they can also be vaccinated. Even if all this is true, it will take at least six months till end of 2021 to vaccinate 70% of the population and get reasonable control of the disease.

Some experts have expressed doubts about the availability of 200 crores of doses of vaccines by the end of 2021. Reason is obvious – there is a global shortage. India is short of inputs that are imported, especially from the US. If this shortage continues, India would not be able to manufacture the doses that the indigenous manufacturers are promising or the government expects from them. Further, the foreign manufacturers are also unlikely to be able to supply the doses that the government expects from them. So, the targets set are unlikely to be fulfilled.

In brief, vaccine shortage will persist for a while so the nation has to follow a queue based on a national priority. So, teachers may have to be vaccinated so that teaching in schools can begin and parents can go to work. Those providing utilities will also have to be vaccinated soon.

The possibility of a third wave and another lockdown needs to be kept in mind since if it materialises there may be a need to change the queue. Now, lockdown is being relaxed when daily infections are around 90,000. The disease is lurking and the virus is most likely mutating. So, there is need for extreme caution. Clearly, a dynamic national and not a sectional or state-wise haphazard vaccination policy is needed.

Arun Kumar is Malcolm Adiseshiah Chair Professor, Institute of Social Sciences. He is author of Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis: Impact of the Coronavirus and the Road Ahead.

courtesy : The Wire